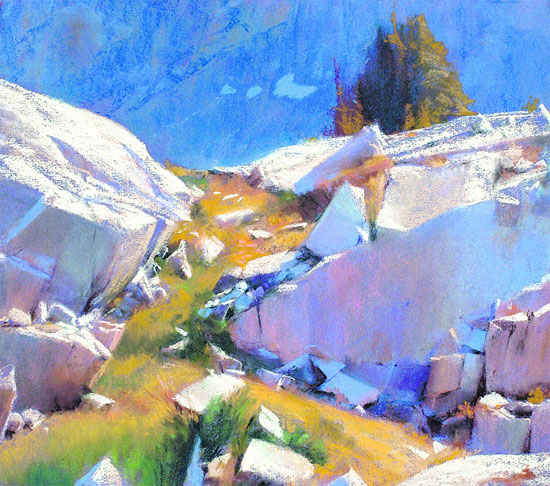

| | | Image title: Afternoon Descent, Artist: Bill Cone, Medium: Pastel on Paper, Size: 16 x 14"

| | | | | | Bill Cone could be a petrologist. After all, he spends hours studying rocks. But Cone, a top production designer at Pixar Animation Studios and a fine artist with a growing reputation and clientele, is already riding two career tracks. Like a circus artist circling under the big top astride two horses, his position is elegant and daring.

Relaxing on the patio of his Moraga home, the elegance rises from his pacing and perspective. He leads an unhurried life, characterized by continuous development more than by arrival. "I'm always headed towards something," he says. And there's a boy-like wonder on his face, the look of an "astonished witness," as he calls himself. He's beguiled not only by light on surfaces, but by his own good fortune; his talented, companionable wife, his two independent children and a career bursting with daily discovery.

Relaxing on the patio of his Moraga home, the elegance rises from his pacing and perspective. He leads an unhurried life, characterized by continuous development more than by arrival. "I'm always headed towards something," he says. And there's a boy-like wonder on his face, the look of an "astonished witness," as he calls himself. He's beguiled not only by light on surfaces, but by his own good fortune; his talented, companionable wife, his two independent children and a career bursting with daily discovery.

This isn't to say that Cone's life has been cushy or pampered. His path out of college required more than a few forays: messengering for Bechtel, playing music in bars, then moving to art, illustration, and finally, animation. There, he discovered the magic of color and the emotional resonance of light and shadow.

This isn't to say that Cone's life has been cushy or pampered. His path out of college required more than a few forays: messengering for Bechtel, playing music in bars, then moving to art, illustration, and finally, animation. There, he discovered the magic of color and the emotional resonance of light and shadow.

"It was the color scripts for Toy Story that changed everything," he says, "As soon as I got the job of production designer on Bug's Life, I assigned myself the task of creating color scripts." The evolution of animator into fine artist had begun. Color scripts, the streamlined storyboards used to describe the look of a film in progress, were inspirational. At the same time, lunchtime bike rides offered an escape from the studio's breakneck pace and put Cone outside into nature. Equipped with color pastels, ("They're like an adult Crayola that breaks and won't hold a point, but they lay down color fast") he realized how dynamic nature is; offering him endless examples of color, texture and light. "Nature is a great teacher," he says.

"It was the color scripts for Toy Story that changed everything," he says, "As soon as I got the job of production designer on Bug's Life, I assigned myself the task of creating color scripts." The evolution of animator into fine artist had begun. Color scripts, the streamlined storyboards used to describe the look of a film in progress, were inspirational. At the same time, lunchtime bike rides offered an escape from the studio's breakneck pace and put Cone outside into nature. Equipped with color pastels, ("They're like an adult Crayola that breaks and won't hold a point, but they lay down color fast") he realized how dynamic nature is; offering him endless examples of color, texture and light. "Nature is a great teacher," he says.

Standing in the doorway bridging animation and hand-done art, Cone refuses to be caught in the which-is-superior argument. "Animation tools have evolved to the point where art created with either technique has expression," he explains. The secret to producing anything with emotional meaning isn't in the machine or tools used, it's in the person. "To come up with the ideas from within, that's human," he says, emphasizing man's innate creativity. "There are simple laws that function in all sorts of circumstances," he continues. He's describing the interplay of light and form, but also a philosophy of life, where finding the commonality of things and people is more important than judging the differences.

Standing in the doorway bridging animation and hand-done art, Cone refuses to be caught in the which-is-superior argument. "Animation tools have evolved to the point where art created with either technique has expression," he explains. The secret to producing anything with emotional meaning isn't in the machine or tools used, it's in the person. "To come up with the ideas from within, that's human," he says, emphasizing man's innate creativity. "There are simple laws that function in all sorts of circumstances," he continues. He's describing the interplay of light and form, but also a philosophy of life, where finding the commonality of things and people is more important than judging the differences.

Cone's communal, fluid perspective is exemplified most fully by the annual trips he makes into the Sierras. Accompanied by 6-10 fellow artists, pack mules, two cooks and their dogs (for essential bear protection-he's brave, but not foolish,) Cone hikes into the mountains for a five-day art-marathon. The daring part comes into play during the evening sharing sessions, when each artist shows the day's work to the others. "People apologize," he says, laughing, "But it's amazing when we choose the same setting, but see something totally different."

Cone's communal, fluid perspective is exemplified most fully by the annual trips he makes into the Sierras. Accompanied by 6-10 fellow artists, pack mules, two cooks and their dogs (for essential bear protection-he's brave, but not foolish,) Cone hikes into the mountains for a five-day art-marathon. The daring part comes into play during the evening sharing sessions, when each artist shows the day's work to the others. "People apologize," he says, laughing, "But it's amazing when we choose the same setting, but see something totally different."

Last April, Cone had a successful one-man show at the Studio Gallery in San Francisco. In fact, it was so successful he has few paintings left in his living room studio...which means it's time for him to straddle the bike and ride into the Lamorinda hills, searching once again for light on rocks.

Last April, Cone had a successful one-man show at the Studio Gallery in San Francisco. In fact, it was so successful he has few paintings left in his living room studio...which means it's time for him to straddle the bike and ride into the Lamorinda hills, searching once again for light on rocks.

|