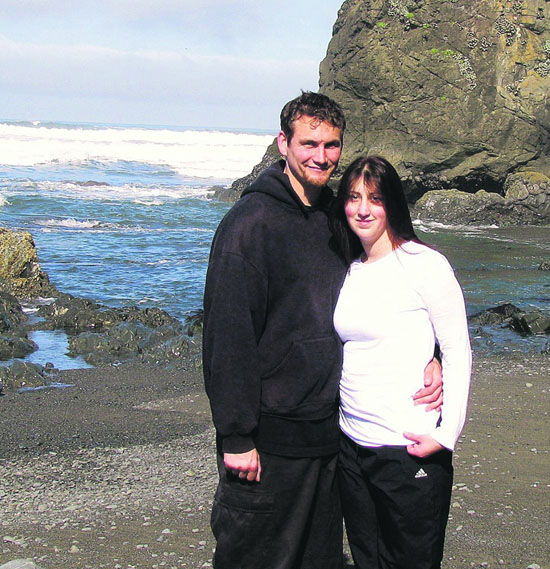

| | | Michael Cadwell and Megan Brubaker Photo provided

| | | | | | Michael Cadwell served four times in Iraq and survived. The trouble is, he brought his terrifying Marine Corps and private security memories back with him. And what's worse, in an ironic, but typical Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) pattern, the nightmarish mental anguish increased the longer he was home.

Sitting comfortably reclined in the living room of his Lafayette duplex, Cadwell has a wide-open, blue-eyed gaze and the comfort of his girlfriend, Megan Brubaker. It's hard to imagine him dodging from room to room, pistol cocked, heart pounding forcefully in his chest, "clearing" every corner and closet. "The first year out I was fine," Cadwell says, "then gradually, I was beyond paranoid."

Sitting comfortably reclined in the living room of his Lafayette duplex, Cadwell has a wide-open, blue-eyed gaze and the comfort of his girlfriend, Megan Brubaker. It's hard to imagine him dodging from room to room, pistol cocked, heart pounding forcefully in his chest, "clearing" every corner and closet. "The first year out I was fine," Cadwell says, "then gradually, I was beyond paranoid."

The fear became so pervasive, he couldn't enter a grocery store without succumbing to panic or anger. Brubaker, a Marriage and Family Therapy student at Cal State East Bay, knew it was only going to get worse.

The fear became so pervasive, he couldn't enter a grocery store without succumbing to panic or anger. Brubaker, a Marriage and Family Therapy student at Cal State East Bay, knew it was only going to get worse.

Cadwell went to the Veteran's Administration (VA) for help. What the military offered was a guilt trip. "There were guys sitting in the same group with me who had had a leg blown off or an arm missing," he remembers, "I'd been over there four times and didn't have a scratch on me." Disappointment in the VA counseling added to his symptoms. "Their job was training us for war, not dealing with it when you get back," Cadwell says.

Cadwell went to the Veteran's Administration (VA) for help. What the military offered was a guilt trip. "There were guys sitting in the same group with me who had had a leg blown off or an arm missing," he remembers, "I'd been over there four times and didn't have a scratch on me." Disappointment in the VA counseling added to his symptoms. "Their job was training us for war, not dealing with it when you get back," Cadwell says.

Brubaker agrees, saying Cadwell had learned he was "supposed to be mad, so he could fight." What's worse, when he returned, he was "taught not to talk about it, because that's how you are strong, how you protect your family." Fortunately for Cadwell, Christina Madlener, the founder and Executive Director of Veterans Resource, came to speak at a class Brubaker was taking.

Brubaker agrees, saying Cadwell had learned he was "supposed to be mad, so he could fight." What's worse, when he returned, he was "taught not to talk about it, because that's how you are strong, how you protect your family." Fortunately for Cadwell, Christina Madlener, the founder and Executive Director of Veterans Resource, came to speak at a class Brubaker was taking.

Veteran's Resource, a community-based non-profit providing counseling for veterans and their families, specializes in EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing). Although Cadwell had doubts, Brubaker insisted he give it a try. "I was trying it out mostly to shut her up," he admits. Today, just over a year later, the comment doesn't faze Brubaker in the least, especially because the therapy worked.

Veteran's Resource, a community-based non-profit providing counseling for veterans and their families, specializes in EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing). Although Cadwell had doubts, Brubaker insisted he give it a try. "I was trying it out mostly to shut her up," he admits. Today, just over a year later, the comment doesn't faze Brubaker in the least, especially because the therapy worked.

Two-hour sessions, focusing on specific memories while sensory stimulation from a vibrating machine and flashing lights reconfigured the connections in his brain, rapidly reduced Cadwell's PTSD. "People that were calmer than me before, now, they get mad before me," he says, sounding surprised. Prior to his tours in Iraq, Cadwell describes himself as "happy-didn't have a care in the world." Then came the rage and paranoia of PTSD. And now? "Happy-but I think things through."

Two-hour sessions, focusing on specific memories while sensory stimulation from a vibrating machine and flashing lights reconfigured the connections in his brain, rapidly reduced Cadwell's PTSD. "People that were calmer than me before, now, they get mad before me," he says, sounding surprised. Prior to his tours in Iraq, Cadwell describes himself as "happy-didn't have a care in the world." Then came the rage and paranoia of PTSD. And now? "Happy-but I think things through."

If it's all so easy, if EMDR is one of the most effective tools for combating war-related PTSD, then why isn't the VA offering it? "It's expensive to change," suggests Brubaker. She points out that implementing new therapies means retraining personnel, reconfiguring decades-old systems, and supplying individual treatment. Not to mention knocking aside what Cadwell believes is the most formidable barricade: the military's steely-jawed, don't talk profile.

If it's all so easy, if EMDR is one of the most effective tools for combating war-related PTSD, then why isn't the VA offering it? "It's expensive to change," suggests Brubaker. She points out that implementing new therapies means retraining personnel, reconfiguring decades-old systems, and supplying individual treatment. Not to mention knocking aside what Cadwell believes is the most formidable barricade: the military's steely-jawed, don't talk profile.

Dr. Gellerman, Clinic Manager at the Mental Health Clinic at VA Sacramento Medical Center, explains why EMDR is not currently available in the Northern California area: "We don't have people trained in it." But he does offer hope for vets interested in receiving the therapy, saying the VA "can fee-basis the patient." If approved, this process operates like a referral, with the VA covering the outside provider's costs.

Dr. Gellerman, Clinic Manager at the Mental Health Clinic at VA Sacramento Medical Center, explains why EMDR is not currently available in the Northern California area: "We don't have people trained in it." But he does offer hope for vets interested in receiving the therapy, saying the VA "can fee-basis the patient." If approved, this process operates like a referral, with the VA covering the outside provider's costs.

The luck Cadwell had in remaining physically unscathed while in Iraq didn't end upon his return. He's still receiving therapy once a week, but his memories are forever changed. His house is clear, his hope is returning, his healing has begun.

The luck Cadwell had in remaining physically unscathed while in Iraq didn't end upon his return. He's still receiving therapy once a week, but his memories are forever changed. His house is clear, his hope is returning, his healing has begun.

|