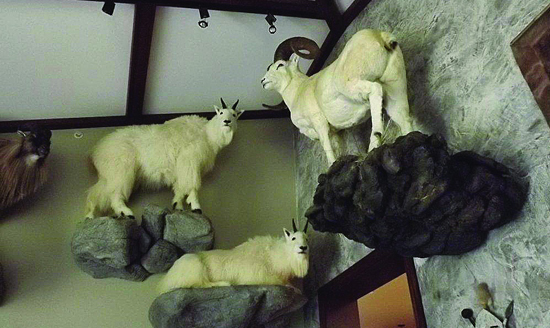

| | | Displays create a museum-like atmosphere in expansive Lamorinda trophy room.

| | | | | | John Doe's is the house that big game built, whose trophies once walked the earth. In fact Doe designed his house several years ago specifically to accommodate what he calls his "passion" for wild game hunting.

Doe is not his real name - he is sensitive that animal activists might take offense. But the Lamorinda man who shared his story, and his very photogenic trophy room, speaks like a naturalist with a reverence for animals both living and dead.

Doe is not his real name - he is sensitive that animal activists might take offense. But the Lamorinda man who shared his story, and his very photogenic trophy room, speaks like a naturalist with a reverence for animals both living and dead.

A tour of Doe's trophy room reveals the depth of his passion. A moose head, nicknamed "Morris," and "Jeffrey," the 8-foot-tall giraffe head, dominate one wall. The remaining animals are preserved whole and seemingly poised to take flight momentarily.

A tour of Doe's trophy room reveals the depth of his passion. A moose head, nicknamed "Morris," and "Jeffrey," the 8-foot-tall giraffe head, dominate one wall. The remaining animals are preserved whole and seemingly poised to take flight momentarily.

An impala, bush buck, stein buck and klipspringer sniff the air for predators. A jackal jumps and claws at a small game bird, while a tahr (Himalayan mountain goat) and a pair of Dall sheep literally climb the walls.

An impala, bush buck, stein buck and klipspringer sniff the air for predators. A jackal jumps and claws at a small game bird, while a tahr (Himalayan mountain goat) and a pair of Dall sheep literally climb the walls.

A menacing Cape buffalo - "a dangerous animal," said Doe - locks eyes with visitors. Doe said there are actually more "closet hunters" in the East Bay than one would think. Just how did a local city boy raised in Oakland, whose father "never hunted a day in his life" become the globe-trotting hunter of today?

A menacing Cape buffalo - "a dangerous animal," said Doe - locks eyes with visitors. Doe said there are actually more "closet hunters" in the East Bay than one would think. Just how did a local city boy raised in Oakland, whose father "never hunted a day in his life" become the globe-trotting hunter of today?

"I think it's genetic," he said simply. Doe's fascination began "out of the blue" watching Mutual of Omaha's Wild Kingdom as a boy. He started fishing with his best friend, whose mother took them on trips. He learned fire arm safety and target shooting with .22 rifles as a Boy Scout.

"I think it's genetic," he said simply. Doe's fascination began "out of the blue" watching Mutual of Omaha's Wild Kingdom as a boy. He started fishing with his best friend, whose mother took them on trips. He learned fire arm safety and target shooting with .22 rifles as a Boy Scout.

"I had to wait until I was old enough to do it [hunting] myself," he said, "then [came] this passion."

"I had to wait until I was old enough to do it [hunting] myself," he said, "then [came] this passion."

An Eagle Scout as well as the father of Eagle Scouts, Doe has imparted the importance and culture of hunting to his sons. Hunters like Doe seek only mature male animals, those which can no longer breed and would likely die of natural causes within a year. "You don't kill anything you are going to waste," he said, which means the meat is always consumed.

An Eagle Scout as well as the father of Eagle Scouts, Doe has imparted the importance and culture of hunting to his sons. Hunters like Doe seek only mature male animals, those which can no longer breed and would likely die of natural causes within a year. "You don't kill anything you are going to waste," he said, which means the meat is always consumed.

One look at his collection shows that Doe has sampled zebra, giraffe, Cape buffalo, and sheep.

One look at his collection shows that Doe has sampled zebra, giraffe, Cape buffalo, and sheep.

Why taxidermy the animal? "Why let its carcass rot?" he replied.

Why taxidermy the animal? "Why let its carcass rot?" he replied.

In 40 years Doe's passion has taken him on trips as far away as New Zealand, Siberia, Alaska, Zimbabwe and Mozambique, and across the country to Texas, Montana and Arizona. He buys lottery permits to hunt out of state. "I keep supporting fish and game," he said.

In 40 years Doe's passion has taken him on trips as far away as New Zealand, Siberia, Alaska, Zimbabwe and Mozambique, and across the country to Texas, Montana and Arizona. He buys lottery permits to hunt out of state. "I keep supporting fish and game," he said.

He explained the lack of available game compared with the number of hunters in California makes this state "no place to hunt."

He explained the lack of available game compared with the number of hunters in California makes this state "no place to hunt."

"I've been out four times [in California] duck hunting, and three times I didn't even shoot," Doe said. "Same thing with deer."

"I've been out four times [in California] duck hunting, and three times I didn't even shoot," Doe said. "Same thing with deer."

African safaris appeal to Doe because of the availability of multiple species to hunt, and puts its cost on par with a paid trip to someplace as close as Montana. A hunting broker handles the required game permits abroad. His overseas party always includes a guide or "professional" hunter, two trackers, and a government official. A portion of the hunting fees go to prevent poaching.

African safaris appeal to Doe because of the availability of multiple species to hunt, and puts its cost on par with a paid trip to someplace as close as Montana. A hunting broker handles the required game permits abroad. His overseas party always includes a guide or "professional" hunter, two trackers, and a government official. A portion of the hunting fees go to prevent poaching.

Although the house is relatively new, Doe's trophy room is already full, and the display has spilled into the family room, where a zebra and three pronghorn antelope heads peer from the wall.

Although the house is relatively new, Doe's trophy room is already full, and the display has spilled into the family room, where a zebra and three pronghorn antelope heads peer from the wall.

"My [taxidermied] deer are downstairs," Doe said. "My Cape buffalo would look great - at least to me - up high on the fireplace," Doe said, "but I'll have to ask my wife."

"My [taxidermied] deer are downstairs," Doe said. "My Cape buffalo would look great - at least to me - up high on the fireplace," Doe said, "but I'll have to ask my wife."

From Wild Game to Wall Mount

From Wild Game to Wall Mount

A taxidermist explains the process

A taxidermist explains the process

Taking an animal from habitat to wall mount is nothing if not time consuming. Taxidermist Forrest Farnsworth of Sebastopol's International Big Game Studio has prepared many of John Doe's collection - a job part art, part science.

Taking an animal from habitat to wall mount is nothing if not time consuming. Taxidermist Forrest Farnsworth of Sebastopol's International Big Game Studio has prepared many of John Doe's collection - a job part art, part science.

It takes three months just to prepare the hide, something Farnsworth jobs out to a tannery in Modesto. After the hide is shaved and salted, and it returns to the taxidermist, it can still take up to eight more months to build what he calls an "anatomically correct" model.

It takes three months just to prepare the hide, something Farnsworth jobs out to a tannery in Modesto. After the hide is shaved and salted, and it returns to the taxidermist, it can still take up to eight more months to build what he calls an "anatomically correct" model.

Farnsworth said thanks to quantum improvements in wildlife photography, animal taxidermy has also improved greatly, down to how head and neck veins stand out. Animal forms come pre-positioned looking left or right, and in various sizes.

Farnsworth said thanks to quantum improvements in wildlife photography, animal taxidermy has also improved greatly, down to how head and neck veins stand out. Animal forms come pre-positioned looking left or right, and in various sizes.

Once a full body animal is mounted over its mannequin, the musculature is enhanced with clay, and a seam is sewn down its backbone. Glass eyes are hand painted and set in modeling clay by Farnsworth's work partner, daughter Laura Stinson.

Once a full body animal is mounted over its mannequin, the musculature is enhanced with clay, and a seam is sewn down its backbone. Glass eyes are hand painted and set in modeling clay by Farnsworth's work partner, daughter Laura Stinson.

Stinson completes the animal makeup around the eyes and nose, even air-brush painting the inside of the ears. She also constructs a small habitat to surround free-standing animals.

Stinson completes the animal makeup around the eyes and nose, even air-brush painting the inside of the ears. She also constructs a small habitat to surround free-standing animals.

Where older taxidermy forms were made of plaster, today's are made of foam and polystyrene - materials similar to those found in furniture. Sunlight, moisture and smoke can affect the look and condition of taxidermy animals. Every five years or so, each animal needs to be dusted and wiped down using a mild cleaning agent and conditioner. That can be done as a house call.

Where older taxidermy forms were made of plaster, today's are made of foam and polystyrene - materials similar to those found in furniture. Sunlight, moisture and smoke can affect the look and condition of taxidermy animals. Every five years or so, each animal needs to be dusted and wiped down using a mild cleaning agent and conditioner. That can be done as a house call.

Doe's giraffe is not the only one Farnsworth has prepared, but Farnsworth said because Doe has hunted on other continents, his collection represents "some unusual stuff." C. Dausman

Doe's giraffe is not the only one Farnsworth has prepared, but Farnsworth said because Doe has hunted on other continents, his collection represents "some unusual stuff." C. Dausman

|