|

|

Published February 11th, 2015

|

How Technology is Changing How We Give

|

|

| By Uma Unni |

|

| Orinda resident Jacquelline Fuller with 12-year-old Daniel, an entrepreneur who built his own phone charging station and charges people's phones for a small fee. Photos provided |

Silicon Valley changed the way we socialize by turning conversations into text message chains and moving our social interactions onto Facebook walls and Instagram profiles. Now, it's changing the way we help those in need.

Orinda resident Jacquelline Fuller sees this every day as the head of Google.org, Google's philanthropic arm. Google.org supports organizations that are finding innovative, entrepreneurial ways to tackle the world's challenges. One such organization is GiveDirectly, a Silicon Valley nonprofit that identifies the poorest of the poor in rural Uganda and Kenya and sends a one-time windfall of $1,000 directly to their cell phones, no strings attached. Surprisingly, it works. "The premise behind GiveDirectly," Fuller explains, "is that poor families know best how to allocate additional capital to address their many needs and opportunities." This goes against the traditional belief that nonprofit agencies are able to make better decisions than the people whom they aim to help.

Orinda resident Jacquelline Fuller sees this every day as the head of Google.org, Google's philanthropic arm. Google.org supports organizations that are finding innovative, entrepreneurial ways to tackle the world's challenges. One such organization is GiveDirectly, a Silicon Valley nonprofit that identifies the poorest of the poor in rural Uganda and Kenya and sends a one-time windfall of $1,000 directly to their cell phones, no strings attached. Surprisingly, it works. "The premise behind GiveDirectly," Fuller explains, "is that poor families know best how to allocate additional capital to address their many needs and opportunities." This goes against the traditional belief that nonprofit agencies are able to make better decisions than the people whom they aim to help.

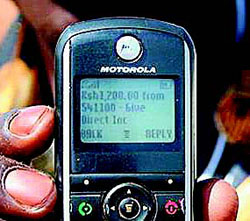

Founded by Harvard economists, and with Fuller as a board member, GiveDirectly currently operates only in Uganda and Kenya. GiveDirectly identifies the particularly needy and sends cash transfers to their mobile phones using a mobile banking technology called M-Pesa. If the recipient has no cell phone, GiveDirectly provides them with a cheap $10 phone for this purpose. The money comes in two installments of $500 over the course of one to two years. Before the money is sent, the family is evaluated to ensure that the recipients are responsible, and preliminary data are recorded on the family's income, health, stress levels (based on cortisol levels), among other things. A subsequent interview records how recipients spent the money (and verifies their stories with other members of the village) and takes new measurements of the same things they measured on the first visit. Data show that GiveDirectly windfalls are put to good use. "According to the data," Fuller adds, "GiveDirectly grants do not affect spending on alcohol or tobacco, and even several months after receiving the grants, earnings are up by 34 percent." Entrepreneurs start businesses, and others invest the money in their children's education and precautionary savings.

Founded by Harvard economists, and with Fuller as a board member, GiveDirectly currently operates only in Uganda and Kenya. GiveDirectly identifies the particularly needy and sends cash transfers to their mobile phones using a mobile banking technology called M-Pesa. If the recipient has no cell phone, GiveDirectly provides them with a cheap $10 phone for this purpose. The money comes in two installments of $500 over the course of one to two years. Before the money is sent, the family is evaluated to ensure that the recipients are responsible, and preliminary data are recorded on the family's income, health, stress levels (based on cortisol levels), among other things. A subsequent interview records how recipients spent the money (and verifies their stories with other members of the village) and takes new measurements of the same things they measured on the first visit. Data show that GiveDirectly windfalls are put to good use. "According to the data," Fuller adds, "GiveDirectly grants do not affect spending on alcohol or tobacco, and even several months after receiving the grants, earnings are up by 34 percent." Entrepreneurs start businesses, and others invest the money in their children's education and precautionary savings.

GiveDirectly's method of gathering data follows a common approach in the scientific and medical fields; they use randomized control tests, providing a level of accuracy which is difficult to attain in the field of philanthropy.

GiveDirectly's method of gathering data follows a common approach in the scientific and medical fields; they use randomized control tests, providing a level of accuracy which is difficult to attain in the field of philanthropy.

Fuller hopes that this quantitative approach can bring a new standard of rigor to philanthropy by providing concrete measures of success or failure. As she explains, "programs that want to take $1 on behalf of the poor must prove they are able to do more with that money than the poor could do by receiving it directly." Because it doesn't try to make decisions for its beneficiaries, GiveDirectly does not carry a heavy administrative overhead and is able to send 90 cents of every dollar donated to their recipients.

Fuller hopes that this quantitative approach can bring a new standard of rigor to philanthropy by providing concrete measures of success or failure. As she explains, "programs that want to take $1 on behalf of the poor must prove they are able to do more with that money than the poor could do by receiving it directly." Because it doesn't try to make decisions for its beneficiaries, GiveDirectly does not carry a heavy administrative overhead and is able to send 90 cents of every dollar donated to their recipients.

Fuller and Google.org were so impressed with the data and results presented by GiveDirectly that they donated $2.4 million to the organization. GiveDirectly's innovative approach to giving is gaining popularity and the organization was recently named one of the two best nonprofits by GiveWell, an organization that ranks nonprofits according to effectiveness and efficiency.

Fuller and Google.org were so impressed with the data and results presented by GiveDirectly that they donated $2.4 million to the organization. GiveDirectly's innovative approach to giving is gaining popularity and the organization was recently named one of the two best nonprofits by GiveWell, an organization that ranks nonprofits according to effectiveness and efficiency.

One of many standout organizations recognized by GiveWell is Charity: Water, which tackles the problem of bringing clean water to remote areas of the world by building hand-operated water pumps. To make sure that none of their pumps fall into disrepair, the organization uses remote sensors to monitor water flow rates in their pumps. They also offer a much more involved role to those who are interested in raising money for the organization. Through their website, anyone can start a campaign to raise money for the cause. Campaigns can range from lemonade stands to sponsored runs, and much crazier ideas (like swimming the San Francisco Bay, or dyeing your hair blue). All of the money raised by these campaigns goes directly toward building and maintaining pumps, and campaign organizers can track exactly where their money goes and how it helps.

One of many standout organizations recognized by GiveWell is Charity: Water, which tackles the problem of bringing clean water to remote areas of the world by building hand-operated water pumps. To make sure that none of their pumps fall into disrepair, the organization uses remote sensors to monitor water flow rates in their pumps. They also offer a much more involved role to those who are interested in raising money for the organization. Through their website, anyone can start a campaign to raise money for the cause. Campaigns can range from lemonade stands to sponsored runs, and much crazier ideas (like swimming the San Francisco Bay, or dyeing your hair blue). All of the money raised by these campaigns goes directly toward building and maintaining pumps, and campaign organizers can track exactly where their money goes and how it helps.

Through things as simple as data collection methods and satellite technology, there are now tools available to tackle the previously intractable challenge of poverty. To learn more about GiveDirectly, visit www.givedirectly.org. To learn more about Charity: Water, visit www.charitywater.org.

Through things as simple as data collection methods and satellite technology, there are now tools available to tackle the previously intractable challenge of poverty. To learn more about GiveDirectly, visit www.givedirectly.org. To learn more about Charity: Water, visit www.charitywater.org.

|

|

| A man holds up his phone showing the GiveDirectly windfall. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|