|

|

|

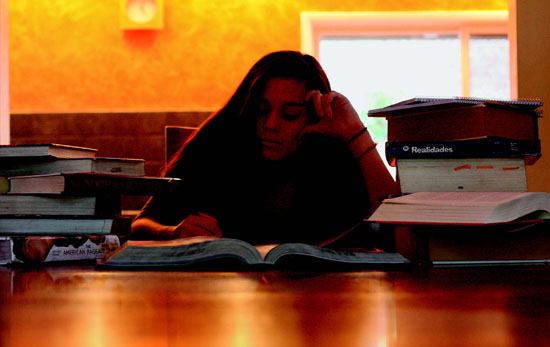

Acalanes High School freshman Elena Mountin hard at work. Photo Uma Unni

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the spring of 2015, students at all four schools in the Acalanes Union High School District took the Stanford Survey of Adolescent School Experiences, more commonly referred to as the "stress test." This survey was administered by the Challenge Success program, a nonprofit group associated with the Stanford Graduate School of Education. The survey gauged student perceptions of a wide variety of subjects, ranging from homework load and school stress to academic integrity and engagement. Based on the results of the survey, the Challenge Success program is working with the school district to create a less stressful and more engaging school environment for students.

The district has a lot of work to do.

The district has a lot of work to do.

According to the survey, 83 percent of Campolindo High School students reported often feeling stressed by school work (Acalanes and Miramonte had similar numbers); 42 percent of Miramonte students suffered from exhaustion, headaches or had trouble sleeping; and 96 percent of Acalanes students admitted to cheating in the past year (cheating was broadly defined by the survey, ranging from copying homework to cheating on tests).

According to the survey, 83 percent of Campolindo High School students reported often feeling stressed by school work (Acalanes and Miramonte had similar numbers); 42 percent of Miramonte students suffered from exhaustion, headaches or had trouble sleeping; and 96 percent of Acalanes students admitted to cheating in the past year (cheating was broadly defined by the survey, ranging from copying homework to cheating on tests).

A natural conclusion to draw from the results is that students are anxious because they care too deeply about school, but further data suggests otherwise. At Acalanes, a mere 9 percent of students felt that they were fully engaged in their academics, while 50 percent of students admitted that they were simply "doing school."

A natural conclusion to draw from the results is that students are anxious because they care too deeply about school, but further data suggests otherwise. At Acalanes, a mere 9 percent of students felt that they were fully engaged in their academics, while 50 percent of students admitted that they were simply "doing school."

If students are not deeply engaged in their academics, then why do they feel so stressed out by school? This could be because students are focused more on outcomes than on real academic engagement. "Students are looking at the end game," says Acalanes principal Allison Silvestri. With acceptance rates dropping rapidly in colleges across the country, students feel the need to differentiate themselves from the pool of applicants however they can, grasping at every extra GPA point, AP class and extracurricular activity they can manage in the hope that these might boost their chances of admission to their preferred schools.

If students are not deeply engaged in their academics, then why do they feel so stressed out by school? This could be because students are focused more on outcomes than on real academic engagement. "Students are looking at the end game," says Acalanes principal Allison Silvestri. With acceptance rates dropping rapidly in colleges across the country, students feel the need to differentiate themselves from the pool of applicants however they can, grasping at every extra GPA point, AP class and extracurricular activity they can manage in the hope that these might boost their chances of admission to their preferred schools.

Amber Li, a junior at Acalanes, frequently worries that if she lets her grades drop, she will be risking her chances of admission at her dream college, University of California, Los Angeles. "It's not only that it's a prestigious college - which it definitely is," she explains. "It's also way more affordable for me to go to school at a UC than a college in a different state."

Amber Li, a junior at Acalanes, frequently worries that if she lets her grades drop, she will be risking her chances of admission at her dream college, University of California, Los Angeles. "It's not only that it's a prestigious college - which it definitely is," she explains. "It's also way more affordable for me to go to school at a UC than a college in a different state."

Although the UC system was designed to provide affordable education for California students primarily, Li worries that the UC system may prefer to accept out-of-state students because they can charge higher tuition fees from them than from California students. This puts greater pressure on California applicants, who feel they must be truly exceptional students to overcome this admissions bias.

Although the UC system was designed to provide affordable education for California students primarily, Li worries that the UC system may prefer to accept out-of-state students because they can charge higher tuition fees from them than from California students. This puts greater pressure on California applicants, who feel they must be truly exceptional students to overcome this admissions bias.

Many students also seek to differentiate themselves on the sports field and the theater stage. One-third of Acalanes students are involved in the music program, and 80 percent play at least one sport. Acalanes students cited sports as the most stressful extra-curricular activity. The survey did not ask why this was the case, but Silvestri speculates that there could be any number of reasons, ranging from parental pressure to hopes of playing sports in college, or even concerns about not having enough time to fit schoolwork into busy sports schedules.

Many students also seek to differentiate themselves on the sports field and the theater stage. One-third of Acalanes students are involved in the music program, and 80 percent play at least one sport. Acalanes students cited sports as the most stressful extra-curricular activity. The survey did not ask why this was the case, but Silvestri speculates that there could be any number of reasons, ranging from parental pressure to hopes of playing sports in college, or even concerns about not having enough time to fit schoolwork into busy sports schedules.

Mia Stripling, an Acalanes junior who is currently taking a full course load that includes four AP/Honors courses, spends six hours completing homework on a typical school night. "I get home around five after softball training, start doing homework at six, and finish around midnight." Her sleep schedule is unpredictable: she gets between four and seven hours of sleep each night, but she describes the latter as less frequent than she would like.

Mia Stripling, an Acalanes junior who is currently taking a full course load that includes four AP/Honors courses, spends six hours completing homework on a typical school night. "I get home around five after softball training, start doing homework at six, and finish around midnight." Her sleep schedule is unpredictable: she gets between four and seven hours of sleep each night, but she describes the latter as less frequent than she would like.

Stripling's experiences match up with the majority of Acalanes students, who get an average of barely six hours of sleep a night, according to the survey. This falls far short of the suggested 9-10 hours teenagers are supposed to get. Silvestri points out that this lack of sleep is "greatly detrimental to students' brain growth," since the human brain does not fully stop developing until age 25, and most brain development takes place during sleep.

Stripling's experiences match up with the majority of Acalanes students, who get an average of barely six hours of sleep a night, according to the survey. This falls far short of the suggested 9-10 hours teenagers are supposed to get. Silvestri points out that this lack of sleep is "greatly detrimental to students' brain growth," since the human brain does not fully stop developing until age 25, and most brain development takes place during sleep.

Dr. Juliana Damon, a local pediatrician, says that her teenage patients come to her with anxiety and depression, at least partially caused by lack of sleep. Some of her patients end up developing stress-induced sleep problems, which only exacerbate the situation. Damon also says that alongside school- and sport-related demands, time-management issues are frequently the culprit.

Dr. Juliana Damon, a local pediatrician, says that her teenage patients come to her with anxiety and depression, at least partially caused by lack of sleep. Some of her patients end up developing stress-induced sleep problems, which only exacerbate the situation. Damon also says that alongside school- and sport-related demands, time-management issues are frequently the culprit.

Along with poor time management, unfocused work habits could also be contributing to the long homework hours students complain about. While doing homework, 44 percent of Acalanes students said they texted their friends, 30 percent watched TV, Netflix and YouTube, and 29 percent went on social media.

Along with poor time management, unfocused work habits could also be contributing to the long homework hours students complain about. While doing homework, 44 percent of Acalanes students said they texted their friends, 30 percent watched TV, Netflix and YouTube, and 29 percent went on social media.

The problem of student stress is far from simple. It cannot be attributed to a single cause, nor can it be solved in a single stroke. However, all four AUHSD schools are making a concerted effort to do what they can to help their students. According to Silvestri, Acalanes is in the early stages of exploring block scheduling, reduced homework loads and even implementation of a homeroom system to provide greater support for individual students.

The problem of student stress is far from simple. It cannot be attributed to a single cause, nor can it be solved in a single stroke. However, all four AUHSD schools are making a concerted effort to do what they can to help their students. According to Silvestri, Acalanes is in the early stages of exploring block scheduling, reduced homework loads and even implementation of a homeroom system to provide greater support for individual students.

More broadly, Silvestri wants students to remember that there is a place for everyone after high school, and it does not need to be a race to the top college or the best sports team. "I wish students knew that opportunities are endless, and each of you will end up where you're supposed to be at the end of your 4-year high school experience. And we just want you to have some fun along the way!"

More broadly, Silvestri wants students to remember that there is a place for everyone after high school, and it does not need to be a race to the top college or the best sports team. "I wish students knew that opportunities are endless, and each of you will end up where you're supposed to be at the end of your 4-year high school experience. And we just want you to have some fun along the way!"

|