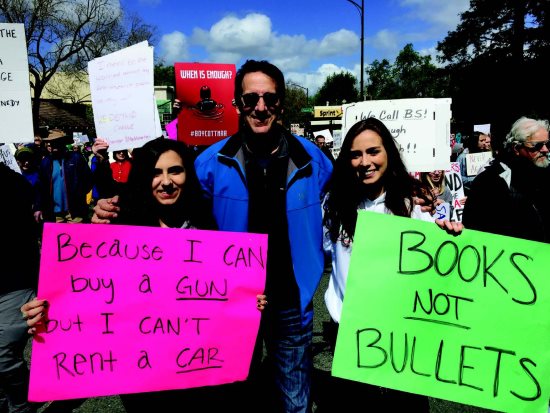

| | | Steve Sposato and daughters Danielle, left, and Jenna at the Walnut Creek march against assault weapons Courtesy Steve Sposato | | | | | | Steve Sposato lost his wife on July 1, 1993 when Gian Luigi Ferri, a disturbed loner, stormed the law offices of Pettit and Martin at 101 California St. in San Francisco, carrying semiautomatic weapons and hundreds of rounds of ammunition. Ferri killed eight and injured six. Sposato has spent the past 25 years on a mission to outlaw the sale of military-style assault weapons in the United States, goading politicians, marching against the National Rifle Association and speaking out at anti-assault weapon rallies.

The agony

The agony

A bulletin flashed across the TV screen at Sposato's Pacific Bell office in San Ramon: a mass shooting in San Francisco. Sposato's wife was in the city, giving a deposition, and he dismissed the frightening possibility. "But in the back of my mind, I had a sense that it was something bad as I left the office." Sposato turned on the television when he got to his Lafayette home and saw a Financial District crime scene. He tried to call his wife; no answer. He tried the office of the law firm where she was being deposed; no answer. He called San Francisco General Hospital; no one knew anything.

A bulletin flashed across the TV screen at Sposato's Pacific Bell office in San Ramon: a mass shooting in San Francisco. Sposato's wife was in the city, giving a deposition, and he dismissed the frightening possibility. "But in the back of my mind, I had a sense that it was something bad as I left the office." Sposato turned on the television when he got to his Lafayette home and saw a Financial District crime scene. He tried to call his wife; no answer. He tried the office of the law firm where she was being deposed; no answer. He called San Francisco General Hospital; no one knew anything.

Sposato tore into the city and pressed for answers. When an officer told Sposato that he should go to 850 Bryant St. and talk to the people in the homicide department, his ill feelings soared. When officials asked him to accompany them to the morgue, Sposato knew.

Sposato tore into the city and pressed for answers. When an officer told Sposato that he should go to 850 Bryant St. and talk to the people in the homicide department, his ill feelings soared. When officials asked him to accompany them to the morgue, Sposato knew.

Jody Sposato was 30.

Jody Sposato was 30.

Sharon O'Roke, the Electronic Data Systems lawyer who took Jody's deposition at the law firm, was Ferri's first victim. "I was handing Jody documents for her to review, and I thought a light from the ceiling had broken and fallen and hit my head," said O'Roke, who took eight gunshots to the right side of her body. "The shooter had kicked in the door to the office and fired 30 rounds of ammunition, targeting who he thought were attorneys, because he ignored the court reporter. After he thought he had killed us all, he left." Jody and lawyer Jack Berman were dead, with O'Roke lying on the conference room floor, unable to move, hearing screams and gunfire in the hall. Ferri killed himself in a stairwell as police honed in.

Sharon O'Roke, the Electronic Data Systems lawyer who took Jody's deposition at the law firm, was Ferri's first victim. "I was handing Jody documents for her to review, and I thought a light from the ceiling had broken and fallen and hit my head," said O'Roke, who took eight gunshots to the right side of her body. "The shooter had kicked in the door to the office and fired 30 rounds of ammunition, targeting who he thought were attorneys, because he ignored the court reporter. After he thought he had killed us all, he left." Jody and lawyer Jack Berman were dead, with O'Roke lying on the conference room floor, unable to move, hearing screams and gunfire in the hall. Ferri killed himself in a stairwell as police honed in.

Early activism

Early activism

His life shattered, Sposato went home in a daze and hugged his 10-month-old daughter Meghan. He read about the firepower that Ferri carried into the building: the ammunition, the handgun and the two TEC-DC9 semiautomatic pistols - the same weapon use by Dylan Klebold in the 1999 Columbine High School massacre. "That's legal? In America? In 1993? And then I got angry. Probably the most deep-seated anger I've ever felt in my life."

His life shattered, Sposato went home in a daze and hugged his 10-month-old daughter Meghan. He read about the firepower that Ferri carried into the building: the ammunition, the handgun and the two TEC-DC9 semiautomatic pistols - the same weapon use by Dylan Klebold in the 1999 Columbine High School massacre. "That's legal? In America? In 1993? And then I got angry. Probably the most deep-seated anger I've ever felt in my life."

He fired off a letter to President Bill Clinton. "What are you going to do about it?" But Sposato did not want his letter to die in the White House mailroom, so he called Senator Dianne Feinstein. She said she would be happy to deliver the letter to the president, but before she hung up, Feinstein mentioned to Sposato that people react to situations like his in one of two ways: those who want to shield themselves, and those who want to make a change. "It was my ah-ha moment. I decided then to do what I could to get these assault weapons off the street."

He fired off a letter to President Bill Clinton. "What are you going to do about it?" But Sposato did not want his letter to die in the White House mailroom, so he called Senator Dianne Feinstein. She said she would be happy to deliver the letter to the president, but before she hung up, Feinstein mentioned to Sposato that people react to situations like his in one of two ways: those who want to shield themselves, and those who want to make a change. "It was my ah-ha moment. I decided then to do what I could to get these assault weapons off the street."

Two days after the phone call, the senator asked Sposato if he would testify before a Senate Judiciary Committee in Washington on Aug. 4. Feinstein told Sposato that it was his opportunity to push for change, to push for an assault weapon ban. And though Feinstein helped frame his remarks, she never told Sposato what to say.

Two days after the phone call, the senator asked Sposato if he would testify before a Senate Judiciary Committee in Washington on Aug. 4. Feinstein told Sposato that it was his opportunity to push for change, to push for an assault weapon ban. And though Feinstein helped frame his remarks, she never told Sposato what to say.

Sposato took Meghan along. "We were supposed to go on at 11, but things went three hours late. I ran out of food. Ran out of diapers. Meghan was crying, she didn't want to be there. I thought, well, I had my moment, I blew it. But at least I tried." Finally, the doors to the chamber opened, Sposato walked to his seat, Meghan settled down, and as he faced the Senate panel he delivered an authentic, riveting performance.

Sposato took Meghan along. "We were supposed to go on at 11, but things went three hours late. I ran out of food. Ran out of diapers. Meghan was crying, she didn't want to be there. I thought, well, I had my moment, I blew it. But at least I tried." Finally, the doors to the chamber opened, Sposato walked to his seat, Meghan settled down, and as he faced the Senate panel he delivered an authentic, riveting performance.

"The image of Steve Sposato testifying before the Judiciary Committee in support of an assault weapons ban with his daughter Meghan on his back has never left me," Feinstein said. "Steve's testimony was incredibly powerful and helpful in moving the ban forward. Here was a man who had the perfect family - a beautiful wife and baby girl - and he told senators how a gunman with easy access to military-style weapons robbed him of that life."

"The image of Steve Sposato testifying before the Judiciary Committee in support of an assault weapons ban with his daughter Meghan on his back has never left me," Feinstein said. "Steve's testimony was incredibly powerful and helpful in moving the ban forward. Here was a man who had the perfect family - a beautiful wife and baby girl - and he told senators how a gunman with easy access to military-style weapons robbed him of that life."

Sposato suppressed nothing as he confronted the committee, with Meghan inserting whimpers and wails at seemingly rehearsed moments. "You're looking at what's left of my family. The sight of our 10-month-old daughter placing dirt on her mother's grave is a sight I pray no other person has to experience. You can't imagine the pain unless you've been in this seat."

Sposato suppressed nothing as he confronted the committee, with Meghan inserting whimpers and wails at seemingly rehearsed moments. "You're looking at what's left of my family. The sight of our 10-month-old daughter placing dirt on her mother's grave is a sight I pray no other person has to experience. You can't imagine the pain unless you've been in this seat."

Nor could Sposato have imagined the effect of his testimony. The media bombarded him. "I learned how Congress is controlled by the NRA, and the means to beat that is through the media. I relentlessly went after the politicians."

Nor could Sposato have imagined the effect of his testimony. The media bombarded him. "I learned how Congress is controlled by the NRA, and the means to beat that is through the media. I relentlessly went after the politicians."

Sposato did the national talk show circuit. He spoke at a press conference with Clinton in the Rose Garden. He hammered politicians every chance he could, and his efforts paid off.

Sposato did the national talk show circuit. He spoke at a press conference with Clinton in the Rose Garden. He hammered politicians every chance he could, and his efforts paid off.

Feinstein's assault weapons ban - part of the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act - passed narrowly in the Senate. With Sposato standing behind him at the White House ceremony, Clinton signed the bill, which he dedicated to Jody and two others.

Feinstein's assault weapons ban - part of the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act - passed narrowly in the Senate. With Sposato standing behind him at the White House ceremony, Clinton signed the bill, which he dedicated to Jody and two others.

"You opened your remarks at the White House by saying that though you were honored to be there, you would rather not have been called to speak under such circumstances. I honor you now for a different reason - your incredible courage. This country cannot thank you enough for the contribution you have made," Clinton wrote in a letter to Sposato.

"You opened your remarks at the White House by saying that though you were honored to be there, you would rather not have been called to speak under such circumstances. I honor you now for a different reason - your incredible courage. This country cannot thank you enough for the contribution you have made," Clinton wrote in a letter to Sposato.

The activism continues

The activism continues

The ban expired in 2004, but Sposato's intensity has not. "I'm still angry. My wife took five in the back. Weapons of war are available in the U.S. and to buy these things doesn't require a background check. It's a failure of government. They're supposed to protect us and they aren't doing it. It's pathetic."

The ban expired in 2004, but Sposato's intensity has not. "I'm still angry. My wife took five in the back. Weapons of war are available in the U.S. and to buy these things doesn't require a background check. It's a failure of government. They're supposed to protect us and they aren't doing it. It's pathetic."

It's not as if Sposato, a lifelong Republican and gun owner, is antigun. "I have no interest in getting rid of the Second Amendment. You want to own a rifle, own it. You want a gun for self-defense, ask the police how to use it." But he insists that assault weapons have got to go.

It's not as if Sposato, a lifelong Republican and gun owner, is antigun. "I have no interest in getting rid of the Second Amendment. You want to own a rifle, own it. You want a gun for self-defense, ask the police how to use it." But he insists that assault weapons have got to go.

Remarried and now with three daughters, Sposato, president of a high-tech consulting firm, said he has faith in the students who are disrupting the establishment after the Parkland, Florida high school shootings, driven by their own anger and the absurdity of seeing their friends getting killed. "They can move CEOs with their vast buying power. And they can make changes in this election. Make guns a pivotal issue, demand universal background checks and an assault weapons ban. Do not stop until you get what you want." He recently delivered the same message to students at Acalanes High School.

Remarried and now with three daughters, Sposato, president of a high-tech consulting firm, said he has faith in the students who are disrupting the establishment after the Parkland, Florida high school shootings, driven by their own anger and the absurdity of seeing their friends getting killed. "They can move CEOs with their vast buying power. And they can make changes in this election. Make guns a pivotal issue, demand universal background checks and an assault weapons ban. Do not stop until you get what you want." He recently delivered the same message to students at Acalanes High School.

The public appears to be listening. American voters support stricter gun laws 66 - 31 percent, the highest level of support ever measured by the independent Quinnipiac University National Poll, taken after the Parkland shootings. Support for universal background checks was itself almost universal, at 97 - 2 percent.

The public appears to be listening. American voters support stricter gun laws 66 - 31 percent, the highest level of support ever measured by the independent Quinnipiac University National Poll, taken after the Parkland shootings. Support for universal background checks was itself almost universal, at 97 - 2 percent.

The lingering effects

The lingering effects

With every Virginia Tech, every Columbine, every Sandy Hook, every Parkland, the images return. "Absolutely, the wounds reopen," O'Roke said. "I feel fearful, I withdraw and I have problems with short-term memory." Now an activist living in Oklahoma City, O'Roke said she experienced years of guilt over Jody's death, feeling that no deposition would have been necessary had she been able to convince her boss to settle Jody's EDS employment claim. "If we had, she would have been alive," O'Roke said. Sposato heard about O'Roke's tortured feelings through a CNN producer he knew. "Steve called me and said that I was only doing my job, and that I had nothing to do with Jody's death. The one responsible was Ferri," said O'Roke, who has never met Sposato. "It was a gesture I will never forget."

With every Virginia Tech, every Columbine, every Sandy Hook, every Parkland, the images return. "Absolutely, the wounds reopen," O'Roke said. "I feel fearful, I withdraw and I have problems with short-term memory." Now an activist living in Oklahoma City, O'Roke said she experienced years of guilt over Jody's death, feeling that no deposition would have been necessary had she been able to convince her boss to settle Jody's EDS employment claim. "If we had, she would have been alive," O'Roke said. Sposato heard about O'Roke's tortured feelings through a CNN producer he knew. "Steve called me and said that I was only doing my job, and that I had nothing to do with Jody's death. The one responsible was Ferri," said O'Roke, who has never met Sposato. "It was a gesture I will never forget."

Sposato agreed that the surreal images remain forever. "I had to tell a 10-month-old that mommy was dead. I'd like to say I've gotten over this, but you never get over it."

Sposato agreed that the surreal images remain forever. "I had to tell a 10-month-old that mommy was dead. I'd like to say I've gotten over this, but you never get over it."

|