| ||||||

And in a way, there was.

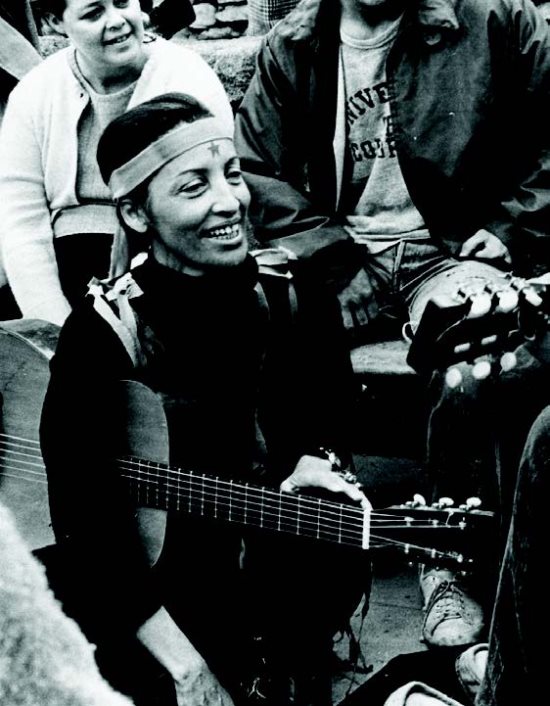

Appearing Sept. 20 at Sweet Thursday Presents, singer/songwriter, author and civil rights activist Betty Reid Soskin drew a sold-out crowd of nearly 200 people. Remarkable for a variety of achievements, Soskin at age 97 is the National Park Service's oldest ranger. Her memoir, "Sign My Name to Freedom" (Hay House, 2018), chronicles a pioneering life from her birth in 1921 in Detroit, Michigan, through growing up in the Deep South with Louisiana Creole parents and rich ancestral history.

The memoir reveals that upon moving to the Bay Area and becoming an adult, Soskin existed on a racial bridge that had her deeply invested in Oakland and Berkeley Black communities and organizations, but also living, working, marrying twice and raising four children in what were, at the time, predominantly all-white neighborhoods. Eventually, Soskin became active in city and state government and white-dominated academia, workers' unions and businesses in Walnut Creek, Berkeley and Oakland.

With limited prompts from moderator Ruth Thornburg, Soskin framed her childhood years. "My father was a craftsman who worked with his father, an eminent builder in New Orleans," she began. Among her family's many achievements were regionally significant buildings and the first banana conveyor used on the docks in Mobile, Alabama. Notable also was the "offense" her father caused by suggesting a white man should address him by his last name and not "Louie," his first name. It was customary - and obviously egregious - racism. Her family had to leave town after her father stood his ground, which explains why she was born and the family lived for the next three years in Michigan, far from their relatives. "I'm glad it's not like that now," said Soskin.

Moving to Oakland in 1927 after their homeland was destroyed that same year by the massive New Orleans floods, the family lived with Soskin's grandfather in East Oakland. Her father worked in the hospitality industry, wearing a red bell cap while working in a hotel. "Our mothers were 50-cents-an-hour domestic servants, taking care of white people's homes and white people's children," she recalled.

Soskin's life as told in her memoir that includes entries from "CBreaux Speaks," the blog she created, is impossible to fit into a 60-minute presentation or a single news article. "You live 97 years, you've got lots of amazing stories," she said. But highlights from the night surely include her description of "trudging through polliwogs and swampland in an area that is now probably where the Oakland Coliseum is," a brief but significant mention about visiting and being honored at the White House at the invitation of Michelle and Barak Obama, and her work with the National Parks.

Soskin was integral to the planning of the Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historical Park in Richmond. Recreating the lost stories of African Americans and Japanese Americans who played vital, until recently unacknowledged roles in the war effort is Soskin's mission. She leads popular presentations at the park three days each week. "Make reservations; we're already booked through October," she suggested.

Reading a chapter from her memoir, Soskin said her life has been a "deliberate progression to her personal political awareness now." Asked during an audience Q&A about education today, Soskin said, "I was educated before Prop. 13 when the public school system in California was the envy of the country. I did grow up with none of the African American literary heroes in my life. But because I had the same heroes my (white) friends were worshipping, I'm less separated out. I was also growing up in a time when the crushing weight of low-expectations was not something I was experiencing. There weren't enough African Americans in the public schools to make new rules against. We were expected to deliver as much as anyone else did. Children growing up now are living under the crushing weight of low expectations."

Lack of diversity, she said, diminishes the nation. "The diversity is where our richness comes. We are enhanced by those differences. To be all of who you are, no matter who you are, is the job of all of us," she said. Later, she added, "I am living in the future that we created back in the '60s. We made that together, all of us did, black and brown and yellow and straight and gay. That I get to give voice to that is such a privilege."

It's hard to resist using the word "divine" when referring to Soskin. To close the evening, this woman who has lived nearly a century and experienced unimaginable social, economic, political and personal transformation, whipped out a mobile device. Soskin, mouthing the words as they played, shared a recording she made of "Sign My Name to Freedom," a song she wrote in 1964. Claiming that she has "lost my sense of future," but is enrolled in the grand improvisation that is life, Soskin has made a discovery. "Time is absolutely precious. Everything I do has to be real, truthful. I now can see the patterns I couldn't see when I was going through them." To Soskin, that there are other people sharing her purpose-to make the world better by reaching to higher points of truth-provides hope and means "we've got it right."

To learn more about Soskin or order her memoir, visit https://www.signmynamebook.com/. To see additional events offered at LLLC, visit www.lllcf.org.

Reach the reporter at: