|

|

Published June 23rd, 2021

|

Matt Biondi - a swimmer, a teacher, a leader

|

|

| By Jon Kingdon |

|

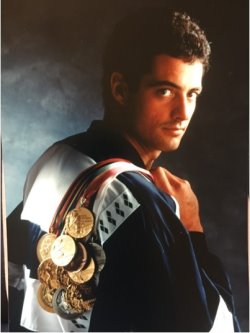

| Biondi speaks to the members of the International Swimmers Alliance in Budapest. Photos provided |

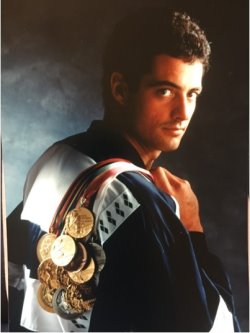

When discussing the life and swimming career of Matt Biondi, one could write almost endlessly about his accomplishments in the pool - but that would be selling short Matt Biondi, the man, and all that went into his successes in and out of the water. In the 1984, 1988 and 1992 Olympics, Biondi won a total of 11 medals (eight gold, two silver and one bronze, setting three individual world records in the 50-meter freestyle and four in the 100-freestyle).

Biondi is in the International Swimming Hall of Fame. the US Olympic Hall of Fame, UC Berkeley Hall of Fame, and the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame in Chicago where you can see Biondi's Olympic medals which have been on display for the last 25 years.

Biondi is in the International Swimming Hall of Fame. the US Olympic Hall of Fame, UC Berkeley Hall of Fame, and the National Italian American Sports Hall of Fame in Chicago where you can see Biondi's Olympic medals which have been on display for the last 25 years.

Like many kids in Lamorinda, Biondi started swimming early in his life. "My sister swam at Moraga Valley Pool," Biondi said. "I tagged along and tried out for the team and ended up setting the Meadow Mini-Meet record. I would swim every summer until I went to high school."

Like many kids in Lamorinda, Biondi started swimming early in his life. "My sister swam at Moraga Valley Pool," Biondi said. "I tagged along and tried out for the team and ended up setting the Meadow Mini-Meet record. I would swim every summer until I went to high school."

Such success does not come easily, but for Biondi it was the foundation of character that he and his siblings learned early from their mother and father: "They gave us their full support in any type of activity we chose to pursue, though we needed to be involved in something that was meaningful and whatever it was, we were out in front and if we made mistakes our parents would be there to support us.

Such success does not come easily, but for Biondi it was the foundation of character that he and his siblings learned early from their mother and father: "They gave us their full support in any type of activity we chose to pursue, though we needed to be involved in something that was meaningful and whatever it was, we were out in front and if we made mistakes our parents would be there to support us.

"When I was 12 years old, I was in the Moraga Valley tennis finals," Biondi remembers. "At one point, I slammed my racket on the net and swore. My mom came out of the stands and pulled me off the court by my ear. She never said a word on the ride home, which was even worse, but I learned the right way to carry yourself."

"When I was 12 years old, I was in the Moraga Valley tennis finals," Biondi remembers. "At one point, I slammed my racket on the net and swore. My mom came out of the stands and pulled me off the court by my ear. She never said a word on the ride home, which was even worse, but I learned the right way to carry yourself."

The ability to make his own choices served Biondi well: "When things got intense at the Olympic level, it was all about me and that's an important message for a lot of parents to understand. I want kids to be the best for 10 years and not at their best when they're 10 years old. They need to let their kids do things on their own early on because they're incredibly capable."

The ability to make his own choices served Biondi well: "When things got intense at the Olympic level, it was all about me and that's an important message for a lot of parents to understand. I want kids to be the best for 10 years and not at their best when they're 10 years old. They need to let their kids do things on their own early on because they're incredibly capable."

Biondi's success in the water enabled him to overcome the usual teenage angst most feel in high school. "Swimming became a place of comfort emotionally for me along with the physical successes."

Biondi's success in the water enabled him to overcome the usual teenage angst most feel in high school. "Swimming became a place of comfort emotionally for me along with the physical successes."

Unlike most of the swimmers who chose to concentrate on swimming or switched over to water polo, Biondi chose to compete in both sports, something not commonly done. "What I did was extremely rare," Biondi said. "There were other athletes in college that competed in both sports, but I was the only one who was a four-year all-American in both swimming and water polo."

Unlike most of the swimmers who chose to concentrate on swimming or switched over to water polo, Biondi chose to compete in both sports, something not commonly done. "What I did was extremely rare," Biondi said. "There were other athletes in college that competed in both sports, but I was the only one who was a four-year all-American in both swimming and water polo."

Despite setting a national high school record in the 50-yard freestyle, Biondi was not recruited that heavily. UCLA wanted him for swimming but Bob Horn, the water polo coach did not think he was good enough for his team and Skip Kenney, the Stanford coach, told Biondi to his face that he didn't have what it took to swim at that level. "Nort Thornton, my coach at Cal was the only coach that was willing to give me a full scholarship and it turned out to be a great partnership."

Despite setting a national high school record in the 50-yard freestyle, Biondi was not recruited that heavily. UCLA wanted him for swimming but Bob Horn, the water polo coach did not think he was good enough for his team and Skip Kenney, the Stanford coach, told Biondi to his face that he didn't have what it took to swim at that level. "Nort Thornton, my coach at Cal was the only coach that was willing to give me a full scholarship and it turned out to be a great partnership."

Biondi learned that revenge is a dish best served cold. "Our water polo won three national championships the four years I was at Berkeley, and I even played for the United States after Seoul in a 1989," Biondi said. "When we played UCLA in water polo, every time I scored a goal, I would make it a point to look over at Horn. After I set three American records in swimming and won two national championships my sophomore year, Kenney walked across the pool deck and shook my hand and said that he was obviously wrong about me."

Biondi learned that revenge is a dish best served cold. "Our water polo won three national championships the four years I was at Berkeley, and I even played for the United States after Seoul in a 1989," Biondi said. "When we played UCLA in water polo, every time I scored a goal, I would make it a point to look over at Horn. After I set three American records in swimming and won two national championships my sophomore year, Kenney walked across the pool deck and shook my hand and said that he was obviously wrong about me."

Competing in the 1984, 1988 and 1992 Olympics was each a unique experience for Biondi. "At the 1984 trials, I went there to have fun and was very relaxed because I didn't expect to win. I saw other swimmers that were acting like they had been pointing towards this race for their entire life. I was leading in the finals, but did not feel like I deserved to win at that point, and finishing in fourth but qualified for the team. It turned out to be a good guide and teaching moment for me. I learned that if I'm going be a champion, I have to start seeing myself on the award stand and when I learned to do that, I was ready."

Competing in the 1984, 1988 and 1992 Olympics was each a unique experience for Biondi. "At the 1984 trials, I went there to have fun and was very relaxed because I didn't expect to win. I saw other swimmers that were acting like they had been pointing towards this race for their entire life. I was leading in the finals, but did not feel like I deserved to win at that point, and finishing in fourth but qualified for the team. It turned out to be a good guide and teaching moment for me. I learned that if I'm going be a champion, I have to start seeing myself on the award stand and when I learned to do that, I was ready."

At the 1988 Olympics, all the press talked about was whether Biondi would break Mark Spitz's record in gold medals, something that Biondi had not concerned himself with. "When I got the bronze medal in my first race, I was thrilled because it was my first individual Olympic medal. Bob Costas then summed up my race by saying that Biondi had failed to eclipse Mark Spitz's record of seven gold medals and had to settle for the bronze and then they went to a commercial. It was really just kind of shocking from that perspective and then things got better as I finished with five golds, a silver and a bronze so that was really nice."

At the 1988 Olympics, all the press talked about was whether Biondi would break Mark Spitz's record in gold medals, something that Biondi had not concerned himself with. "When I got the bronze medal in my first race, I was thrilled because it was my first individual Olympic medal. Bob Costas then summed up my race by saying that Biondi had failed to eclipse Mark Spitz's record of seven gold medals and had to settle for the bronze and then they went to a commercial. It was really just kind of shocking from that perspective and then things got better as I finished with five golds, a silver and a bronze so that was really nice."

Starting in 1989, Biondi and Tom Jager brought professional swimming to the United States for the first time with swimsuit contracts, matches races and appearance events which did not set well with USA Swimming. According to Biondi, "They did not support me as a pro athlete, and I have evidence that they actively suppressed my ability to perform at the Olympics." Still, at the 1992 Olympics Biondi won two more gold medals in the relays and a silver in the 50-meter freestyle. Most importantly, he took on a strong supporting role with the younger swimmers like Summer Sanders who had been expected to win a slew of gold medals that year.

Starting in 1989, Biondi and Tom Jager brought professional swimming to the United States for the first time with swimsuit contracts, matches races and appearance events which did not set well with USA Swimming. According to Biondi, "They did not support me as a pro athlete, and I have evidence that they actively suppressed my ability to perform at the Olympics." Still, at the 1992 Olympics Biondi won two more gold medals in the relays and a silver in the 50-meter freestyle. Most importantly, he took on a strong supporting role with the younger swimmers like Summer Sanders who had been expected to win a slew of gold medals that year.

"Summer had her five events, and she was getting beat by the Chinese, who had numerous swimmers testing positive for doping within two years, but the press was hammering her because she kept losing. After she got the silver medal in the 200 IM, she was sitting there, crying with her head down, in her Olympic sweats with an Olympic silver medal around her neck. I walked over and I just said `I'm proud of you. There are millions of young girls in America that have been inspired by you and you've got one more race, and just go out and do your best,' though she never looked up and didn't stop crying. Summer ended up winning that race, leading from start to finish.

"Summer had her five events, and she was getting beat by the Chinese, who had numerous swimmers testing positive for doping within two years, but the press was hammering her because she kept losing. After she got the silver medal in the 200 IM, she was sitting there, crying with her head down, in her Olympic sweats with an Olympic silver medal around her neck. I walked over and I just said `I'm proud of you. There are millions of young girls in America that have been inspired by you and you've got one more race, and just go out and do your best,' though she never looked up and didn't stop crying. Summer ended up winning that race, leading from start to finish.

"Our Olympic team was gathering for the last time and Summer was like in a daze and when she saw me, she hurried over and gave me a big hug and she whispered in my ear,

"Our Olympic team was gathering for the last time and Summer was like in a daze and when she saw me, she hurried over and gave me a big hug and she whispered in my ear,

`I never could have done it without you.' I had been kind of on the outside so that was a real turning point for me and encapsulated my career. I had started by watching and learning from people and then ending by being able to help somebody do a little bit better."

`I never could have done it without you.' I had been kind of on the outside so that was a real turning point for me and encapsulated my career. I had started by watching and learning from people and then ending by being able to help somebody do a little bit better."

So upset at his mistreatment, Biondi left swimming and began to utilize his degree in Political Economy of Industrialized Societies to teach both history and math.

So upset at his mistreatment, Biondi left swimming and began to utilize his degree in Political Economy of Industrialized Societies to teach both history and math.

Though he stopped swimming competitively, Biondi still found a way to stay connected with the water. "I had more than a dozen experiences with dolphins, right whales, orcas and even fin whales in the Sea of Cortez. I was on a research boat for about five years out of Hawaii swimming with humpback whales underwater which I like to show when I speak to young groups."

Though he stopped swimming competitively, Biondi still found a way to stay connected with the water. "I had more than a dozen experiences with dolphins, right whales, orcas and even fin whales in the Sea of Cortez. I was on a research boat for about five years out of Hawaii swimming with humpback whales underwater which I like to show when I speak to young groups."

Being in the zone is described as the pinnacle of achievement for an athlete and characterizes a state in which an athlete performs to the best of his or her ability. It's a rare situation when it absolutely comes together for a competitor.

Being in the zone is described as the pinnacle of achievement for an athlete and characterizes a state in which an athlete performs to the best of his or her ability. It's a rare situation when it absolutely comes together for a competitor.

Despite being so successful, when Biondi looks back, he can only find one time when everything came together in every aspect of his performance. "It's called optimal experience and it's about a time I had where I felt in complete mastery," Biondi said. "It only happened once. It was so strong and powerful; it just consumed my whole body and I had nothing but endless energy. It was at the Olympic trials in 1988 in Austin, Texas and it was the fastest 100-meters I ever swam. When I look back on my accomplishments, it's things like that which I find to be more special than my medal count."

Despite being so successful, when Biondi looks back, he can only find one time when everything came together in every aspect of his performance. "It's called optimal experience and it's about a time I had where I felt in complete mastery," Biondi said. "It only happened once. It was so strong and powerful; it just consumed my whole body and I had nothing but endless energy. It was at the Olympic trials in 1988 in Austin, Texas and it was the fastest 100-meters I ever swam. When I look back on my accomplishments, it's things like that which I find to be more special than my medal count."

Biondi recently announced the formation of the International Swimmers Alliance (ISA) whose goal is to improve personal and economic opportunities for all swimmers and increase their negotiating power. So far, the alliance is made up of 120 world-class swimmers from 31 countries.

Biondi recently announced the formation of the International Swimmers Alliance (ISA) whose goal is to improve personal and economic opportunities for all swimmers and increase their negotiating power. So far, the alliance is made up of 120 world-class swimmers from 31 countries.

The main issue as Biondi sees it is "power, control and the flow of money."

The main issue as Biondi sees it is "power, control and the flow of money."

"The Olympics in Tokyo were scheduled to make over $7 billion in revenue, which is up from $5 billion from the Olympics in Rio, and it's not unreasonable for the athletes to share in part of that," Biondi said. "We want to know how the money is being generated and where it's going and then ultimately, how can we share this revenue with the athletes who are performing and who are the show and who are the ones that people are paying to see."

"The Olympics in Tokyo were scheduled to make over $7 billion in revenue, which is up from $5 billion from the Olympics in Rio, and it's not unreasonable for the athletes to share in part of that," Biondi said. "We want to know how the money is being generated and where it's going and then ultimately, how can we share this revenue with the athletes who are performing and who are the show and who are the ones that people are paying to see."

Like his parents, Biondi has allowed his kids to make their own choices as well: "My oldest son, Nate, didn't start swimming until his sophomore year in the high school he just graduated from in Berkeley. He was a walk-on and made the sprint relay team that won the NCAAs this year. Lucas is 18 and plays volleyball for the Spike and Serve Club in Honolulu. My daughter Makena is with me and will be a freshman at Calabasas High this year."

Like his parents, Biondi has allowed his kids to make their own choices as well: "My oldest son, Nate, didn't start swimming until his sophomore year in the high school he just graduated from in Berkeley. He was a walk-on and made the sprint relay team that won the NCAAs this year. Lucas is 18 and plays volleyball for the Spike and Serve Club in Honolulu. My daughter Makena is with me and will be a freshman at Calabasas High this year."

With all that is going on, Biondi still finds a release in the pool: "I don't like to compete anymore, but I still try and keep in shape and will swim three days a week with Conejo Valley Multi Sport Masters."

With all that is going on, Biondi still finds a release in the pool: "I don't like to compete anymore, but I still try and keep in shape and will swim three days a week with Conejo Valley Multi Sport Masters."

So, as he has done since he put his first foot in the water, Biondi continues to take the long-term perspective in all his pursuits.

So, as he has done since he put his first foot in the water, Biondi continues to take the long-term perspective in all his pursuits. |

|

| Matt Biondi with his 11 Olympic medals. Photos provided |

|

|