| | Published October 27th, 2021

| Preschool waitlists continue to grow as directors struggle to find and keep staff

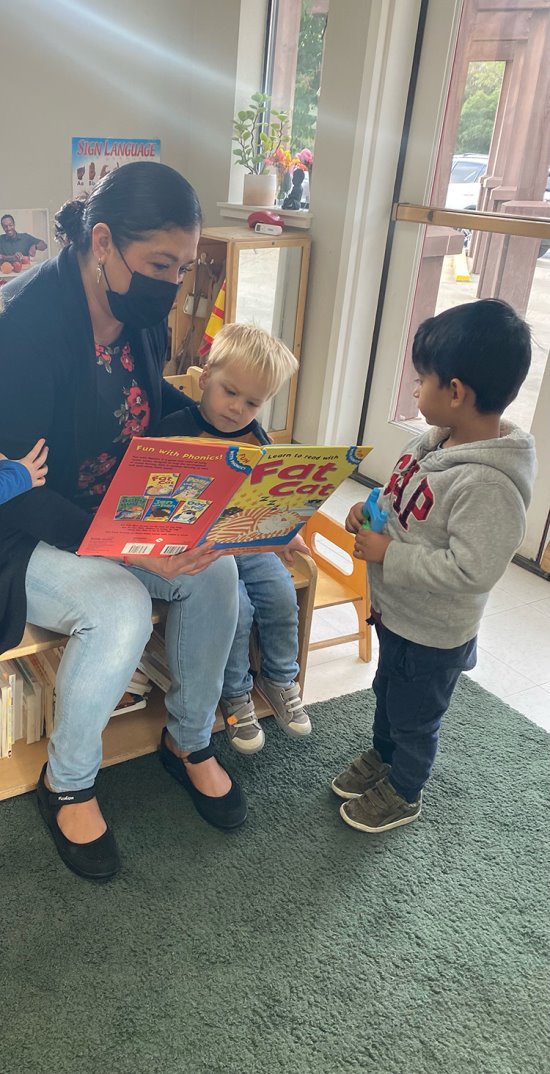

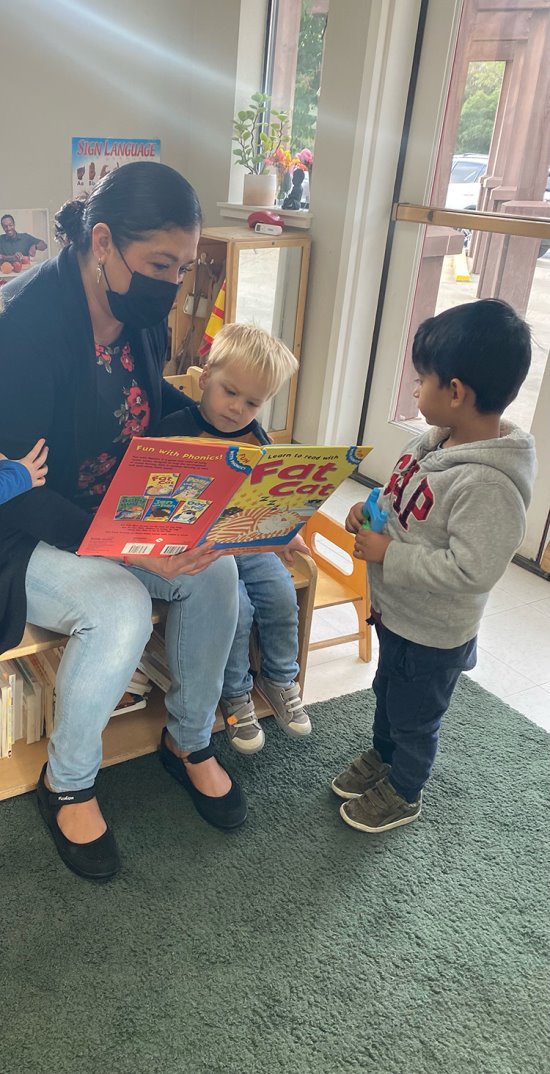

| | | By Sharon K. Sobotta |  | | Soledad Lascon reads with children at St. John's Preschool in Orinda. Photo Sharon K. Sobotta |

After working in her family's restaurant in Martinez for as long as she can remember, Soledad Lascon pivoted to a job as a cook at St. John's preschool in Orinda when her youngest child was born just before the pandemic. The site director Maria Rios noticed a sparkle in Lascon's eye as she served the preschoolers meals and snacks. This prompted Rios to encourage Lascon to take child care units while cooking, and ultimately helped her forgo a teacher shortage.

"Once I got there and started cooking, I realized I really loved working with kids. I followed Maria's advice and went to DVC," Lascon said. "Since I finished work by 12, I had plenty of time in a day to begin completing my units."

"Once I got there and started cooking, I realized I really loved working with kids. I followed Maria's advice and went to DVC," Lascon said. "Since I finished work by 12, I had plenty of time in a day to begin completing my units."

In August when St. John's Preschool lost a teacher to a new opportunity, Lascon moved out of the kitchen and into the classroom.

In August when St. John's Preschool lost a teacher to a new opportunity, Lascon moved out of the kitchen and into the classroom.

"I love it," Lascon said. "When my own child looks at my phone and sees preschool pictures, he's jealous."

"I love it," Lascon said. "When my own child looks at my phone and sees preschool pictures, he's jealous."

Lascon's youngest child is among the dozens of children on the waitlist for the school, which is licensed to serve 48 children and is at full capacity. If not for Lascon's willingness to make a professional pivot, Rios might've found herself in the increasingly familiar struggle so many preschool directors are facing.

Lascon's youngest child is among the dozens of children on the waitlist for the school, which is licensed to serve 48 children and is at full capacity. If not for Lascon's willingness to make a professional pivot, Rios might've found herself in the increasingly familiar struggle so many preschool directors are facing.

"Thank goodness Soledad was ready to jump into the classroom when another teacher gave notice," Rios said. "I feel super lucky to have dodged the bullet that so many other schools are experiencing (with staff turnover and staff retention)."

"Thank goodness Soledad was ready to jump into the classroom when another teacher gave notice," Rios said. "I feel super lucky to have dodged the bullet that so many other schools are experiencing (with staff turnover and staff retention)."

Rios has worked at the preschool for two decades and has been in the director role for a few years. Like all of the six staff members at the preschool, Rios commutes in from a few towns away every day.

Rios has worked at the preschool for two decades and has been in the director role for a few years. Like all of the six staff members at the preschool, Rios commutes in from a few towns away every day.

"I love caring for children in this community and I would love to live in this community, because the school district is just phenomenal," Rios said. "But I can't afford it."

"I love caring for children in this community and I would love to live in this community, because the school district is just phenomenal," Rios said. "But I can't afford it."

Rios says she counts her blessings to have a job she loves, working with a community of children she adores. Of course, she says she's also aware of class disparities. "Sometimes we think we've evolved from these issues, but people of color are (in many cases) having to struggle so much more," Rios said.

Rios says she counts her blessings to have a job she loves, working with a community of children she adores. Of course, she says she's also aware of class disparities. "Sometimes we think we've evolved from these issues, but people of color are (in many cases) having to struggle so much more," Rios said.

Rios' 4-year-old is a student at St. John's preschool. When the enrollment numbers allow for it, teachers have the option of enrolling their own children in the preschool. However, since the pandemic, the demand far outweighs the availability of classroom space. "We have an incredible wait list," Rios said. "It seems like lots of families made their way over to Lamorinda from San Francisco and Oakland and are now desperate to find care."

Rios' 4-year-old is a student at St. John's preschool. When the enrollment numbers allow for it, teachers have the option of enrolling their own children in the preschool. However, since the pandemic, the demand far outweighs the availability of classroom space. "We have an incredible wait list," Rios said. "It seems like lots of families made their way over to Lamorinda from San Francisco and Oakland and are now desperate to find care."

Down the road, at The Child Day School in Moraga, Director Emile Delgado-Olsen has around 100 children on the waitlist. The preschool has around 70 students but is licensed for 84 children. Why aren't there more children in the classroom and fewer on the waitlist? "We need more staff," Delgado-Olsen said.

Down the road, at The Child Day School in Moraga, Director Emile Delgado-Olsen has around 100 children on the waitlist. The preschool has around 70 students but is licensed for 84 children. Why aren't there more children in the classroom and fewer on the waitlist? "We need more staff," Delgado-Olsen said.

There are 16 staff in total at The Child Day School, but Delgado-Olsen would love to have 18. The pandemic changed operations and protocols for places like TCDS, making the need for staff higher in order to accommodate the growing list of students. For example, in pre-pandemic times, all children played in a common area while they waited for the official preschool day to begin. "Now we don't mix kids from different classrooms. That way if there is a positive case in one classroom, we can quarantine that classroom without closing down the entire school."

There are 16 staff in total at The Child Day School, but Delgado-Olsen would love to have 18. The pandemic changed operations and protocols for places like TCDS, making the need for staff higher in order to accommodate the growing list of students. For example, in pre-pandemic times, all children played in a common area while they waited for the official preschool day to begin. "Now we don't mix kids from different classrooms. That way if there is a positive case in one classroom, we can quarantine that classroom without closing down the entire school."

Delgado-Olsen can happily work around these logistical adjustments if he can keep qualified teachers, who've completed 12 child care units, in the classroom. While Delgado-Olsen knows of many other preschools with long waitlists of children and a shortage of teachers, he says the off-the-beaten path location of Moraga, makes it extra challenging.

Delgado-Olsen can happily work around these logistical adjustments if he can keep qualified teachers, who've completed 12 child care units, in the classroom. While Delgado-Olsen knows of many other preschools with long waitlists of children and a shortage of teachers, he says the off-the-beaten path location of Moraga, makes it extra challenging.

"This field is losing a lot of really good qualified teachers because they are getting priced out. If you're not already familiar with this area, you're not likely to drive an extra 30 minutes to get to Moraga."

"This field is losing a lot of really good qualified teachers because they are getting priced out. If you're not already familiar with this area, you're not likely to drive an extra 30 minutes to get to Moraga."

Delgado-Olsen says his staff earns between $20-$24 per hour depending on units and experience. While the wage is higher than service jobs, he acknowledges it's difficult to make ends meet on that wage in the Lamorinda area.

Delgado-Olsen says his staff earns between $20-$24 per hour depending on units and experience. While the wage is higher than service jobs, he acknowledges it's difficult to make ends meet on that wage in the Lamorinda area.

"I wish there was a program that offered affordable housing to educators and caregivers or even (accessory) taxes that somehow went directly to teachers who wanted to live in the communities they're teaching in," Delgado-Olsen said, while reflecting on the difficult place educators are in. The salaries of preschool teachers who are primary breadwinners qualifies many of them for housing. Yet in Lafayette, the below market units on the city's website, the Towne Center, has a waiting list for those earning less than $47,000. The site manager indicated a long waitlist for affordable units, while units available at the regular rate of $4,400 were readily available.

"I wish there was a program that offered affordable housing to educators and caregivers or even (accessory) taxes that somehow went directly to teachers who wanted to live in the communities they're teaching in," Delgado-Olsen said, while reflecting on the difficult place educators are in. The salaries of preschool teachers who are primary breadwinners qualifies many of them for housing. Yet in Lafayette, the below market units on the city's website, the Towne Center, has a waiting list for those earning less than $47,000. The site manager indicated a long waitlist for affordable units, while units available at the regular rate of $4,400 were readily available.

Of all of the uncertainties in the preschool business, Delgado-Olsen knows one thing for sure: There's an influx of families with children eager to get into preschool in the Lamorinda area. And, until there's more staff, it'll be difficult to accommodate more children.

Of all of the uncertainties in the preschool business, Delgado-Olsen knows one thing for sure: There's an influx of families with children eager to get into preschool in the Lamorinda area. And, until there's more staff, it'll be difficult to accommodate more children.

"Most preschools are hanging on by a thread these days. I feel very lucky to have the team and community we have at The Child Day School," Delgado-Olsen said. "And we're definitely desperate to hire."

"Most preschools are hanging on by a thread these days. I feel very lucky to have the team and community we have at The Child Day School," Delgado-Olsen said. "And we're definitely desperate to hire." |

| | | | | | | | | | | | |